It has been a long time since I ruminated on Greek art. Admittedly, not as long as the 2500 or so years since those works were created, but a while nonetheless. Lately I’ve been reminded of my one-time specialty as I provide SMS-text-format Cliffs Notes on ancient masterpieces to a friend trying to squeak by in a Gen-Ed art history course, and it’s made me recall perhaps my favorite artist of all time (WHOA sweeping hyperbolic declaration, but why not.)

Exekias was a badass. Some background (not sourced in proper Chicago Style because, though I could, mercifully blogs are free from the constraints of footnotes, so let’s just rap about it): Exekias lived in the 6th century BCE. He painted on vases. It’s decidedly unglamorous. This isn’t the Sistine Ceiling; it ain’t even the dinky little Mona Lisa. They’re just… pots, with a couple of figures painted on the side. What’s the big deal, you say?

First off, we know this guy’s name. Go to any museum and you’ll find endless anonymous red-and-black pottery. We know who Exekias was because he was one of the first of his kind to sign his work. Signing your work! Not only was this good personal branding, but it distinguished Exekias from the nameless hordes. Where others may have been simple, dime-a-dozen craftsmen or artisans, he was an Artist worthy of a name, and memorialized himself as such.

But what makes these pithy little pots so indelible is the innovation Exekias brought to his subject matter. Previous works of this kind depicted myths and gods and scenes of revelry. There were a standard set of stories and standard ways to portray them. If you were painting the Calydonian Boar Hunt, you simply painted a procession of people with spears, and of course a boar. You painted like a pictograph, so that your subject could most easily be discerned.

Unless you were Exekias. To wit, there is a story in the Iliad about Ajax. After the great hero Achilles dies, Ajax and Odysseus beset the Trojans to retrieve their friend’s body in order to give him a proper burial. They succeed, but then a scuffle ensues over who gets to keep Achilles’ armor as recognition for their actions. When a physical competition yields a tie, both men plead their case. Odysseus is well-known for his quick tongue, and predictably wins the armor. Furious and ashamed, Ajax falls upon his own sword. The story is called “The Suicide of Ajax.”

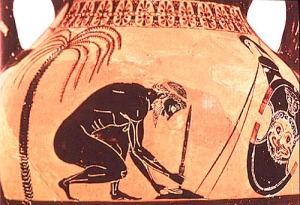

It’s a well-known trope, and the common way of showing it was quite literally Ajax impaled on his own sword. Exekias did this:

Image from uncg.edu: http://www.uncg.edu/cla/myth/ajax.htm

At first you’re not sure what it is. But there’s a man kneeling on the ground, solemnly settling a sword blade-up in a mound of sand, his armor resting to the side. This was heretofore unseen. It isn’t a showy moment, but what my college professor called “the moment before the moment.” There is no melodramatic Ajax bleeding to death on his own sword, but a hopeless and tragic figure calmly assembling the method of his own death. His armor, the symbol of his life, is discarded, and he kneels naked and humbled, and you the viewer are compelled to think about what might be going through poor Ajax’s head at this terrible moment. THAT is the impact of Exekias.

While the Suicide of Ajax is my favorite, Exekias has a few great also-rans as well. His painting of Achilles and Penthesilea mines another rich psychological drama: the Amazon (female) warrior Penthesilea met Achilles on the battlefield in the Trojan War (I guess the Amazons fought for the Trojans? I was always more about the art than the literature, I don’t know.) He slew her, like the killing machine he was, but in the instant his spear pierced her heart, their eyes met and Achilles fell immediately and madly in love with the woman he was that very moment killing. Have you ever?! I mean, the Greeks had a penchant for the over-the-top, yes, but it’s an intense moment. When you’ve been staring at vase after vase showing, say, a courtesan bathing, something this passionate certainly has an impact, and Exekias was intent on capturing it.

Image from Berkeley.edu: http://shelton.berkeley.edu/mymyth/pics23/TB9901190523.jpg

Another famous one of Exekias’s shows Achilles and Ajax (in better days) seated and playing a board game, their armor cast to the side. In the midst of the Trojan War, the two friends are just unwinding with a little game of dice. Exekias mines not the tragedy but the tension of war; not the battle, but the waiting for the battle to commence. Let others show the carnage, the battle, the heroics; but here examine two friends maintaining some semblance of normal life under severely heightened circumstances. If The Suicide of Ajax was the moment before the moment, this is the un-moment.

Image from Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Akhilleus_Aias_MGEt_16757.jpg

Basically everything we watch and read and listen to is like this nowadays. Yes, we still love the spectacle, the blood and action and sex. But as a culture we are deeply infatuated with what Faulkner called “the problems of the human heart in conflict with itself.” Humanity, in a word. This is what makes Exekias so timeless, and what makes the humanities as a course of study still worthwhile, even if no one will pay you any money for it.